A Short History of the Galápagos Tortoise in Celebration of World Turtle Day

Earlier today, we celebrated World Turtle Day with a special episode of Field Transmissions featuring world-renowned Giant Tortoise expert and Galápagos Conservancy Vice President of Science and Conservation Dr. James Gibbs.

Watch the recording below, and read on to learn more about the history of Giant Tortoise population collapse and restoration in the Galápagos Archipelago.

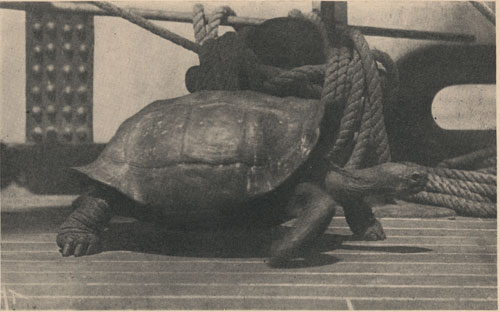

In 1535, a lost Portuguese friar drifted in the Eastern Pacific Ocean toward an undocumented cluster of remote volcanic islands located approximately 600 miles off the western coast of the South American continent. Upon setting foot onto the alien soil, Tomás de Berlanga noted that the inhospitable terrain — inhabited only by birds, seals, and reptiles — was “worthless” and had “not the power of raising a little grass.” For a representative of a powerful European empire, these small spits of land were of no consequence. Berlanga’s report to the king of Spain did not even reference the islands by name. It wasn’t until 1570 that a map was published featuring the Archipelago for the first time, and bestowing upon it a title that would last through the ages: “Insulae de los Galopegos” or Islands of the Saddlebacked Tortoises.

For the next 400 years, this isolated archipelago — and the estimated 1 million Giant Tortoises for which it was named — would be fundamentally changed by the most influential species on Earth: humans.

Due to its unique geographic location, Galápagos served as a convenient outpost throughout the 18th century for pirates and whalers who came to the Islands in search of shelter and resources. This spelled disaster for the 15 species of Giant Tortoises native to the Archipelago, which were collected and killed by the tens of thousands to provide an easy meal to the hungry sailors.

Decades of this bloody harvest led to near-total population collapse for the Giant Tortoises of Galápagos and robbed the island habitats of their critical ecosystem engineers. Once wild numbers had fallen so significantly that tortoises were no longer viewed as a reliable source of food, invasive goats were introduced in their stead, and many of the few tortoises left were rounded up for oil.

By the beginning of the 1900s, the delicate ecosystems of Galápagos were nearly unrecognizable. Introduced goats had quickly reproduced in their new habitat and were decimating native plants. Non-native rats, arriving as stowaways on visiting ships, had also taken up residence on the islands and were devouring the eggs and young of the remaining tortoises. It wasn’t until the 1950s that the idea of “conserving” these islands and their wildlife became a topic of conversation, and a number of scientific expeditions were dispatched to the archipelago, returning with vast collections of data and reports to share. Then, in 1959 the Ecuadorian government passed a landmark law creating the Galapagos National Park. For the first time since its discovery, the Galápagos Archipelago was afforded some measure of protection.

Of course, for the iconic Galápagos Giant Tortoise, these protections were not enough. Centuries of depredation had pushed these animals to the precipice of extinction, and immediate action was necessary to ensure they wouldn’t fade into permanent oblivion. In 1965, the Galapagos National Park Directorate opened two Giant Tortoise breeding centers, with the hope of launching a first-of-its-kind captive breeding and rearing operation aimed at restoring Giant Tortoise populations to their historic numbers in the wild.

What followed was one of the most successful species rewilding efforts in human history.

The Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative (GTRI) — now known as Iniciativa Galápagos — is a decades-long partnership between the Galápagos National Park Directorate and Galápagos Conservancy dedicated to the restoration of the unique and fragile ecosystems of the Galápagos Archipelago. Through this initiative, we have combined world-class scientific expertise with research-based conservation management techniques to facilitate the successful return of the Galápagos Giant Tortoises to their native habitats. Although we have lost two distinct species to extinction — the Floreana Giant Tortoise and Lonesome George’s Pinta Giant Tortoise species — our efforts have achieved some truly incredible conservation milestones:

- In the early 1990s, captive-bred Española Giant Tortoises were repatriated to their home island for the first time as part of a breeding effort starting with just 15 remaining individuals.

- In 2006, invasive Goats, Donkeys, and Pigs were eliminated from Pinta, Northern Isabela, and Santiago Islands.

- Invasive Black Rats, a species known to predate upon tortoise eggs and hatchlings, were eradicated from Pinzon Island in 2012.

- In 2016, we completed the first-ever comprehensive population survey of the San Cristóbal Giant Tortoise population, revealing an estimated 6,700 individuals, an incredible increase from the estimated 500-700 in the early 1970s.

- By the end of 2017, over 7,000 juvenile, captive-bred tortoises had been returned to their native islands – including Española, Isabela, Pinzón, San Cristóbal, Santa Cruz, and Santiago.

- In 2019, we located a lone female Tortoise on Fernandina Island. Later genetic testing confirmed she was a Fernandina Giant Tortoise, a species believed extinct for over 100 years.

- In 2020, we ended a 55-year captive breeding program for the Española Giant Tortoise after it was deemed no longer necessary, and returned the original 15 tortoises – including Diego the world-famous Super Tortoise – back to their home.

- In 2021, we completed a first-ever comprehensive population census of Alcedo Volcano on Isabela Island and located and marked over 4,700 tortoises, numbers showing this to be the healthiest population in the Archipelago.

- Also in 2021, we completed the final phase of the “Plan for the Introduction of Giant Tortoises to Santa Fe,” an ambitious species introduction project aimed at ecological restoration on Santa Fe Island.

- In March of 2022 we completed the first of two expeditions back to Fernandina Island to locate another living Fernandina Giant Tortoise, with the hope of establishing a captive breeding program to save this species from extinction.

In many ways, the story of the Galápagos Islands is indelibly tied to that of the very tortoises for which they were named. Human actions brought these islands and their scaly residents to the very brink of total collapse, but it is human ingenuity, compassion, and collaboration that have now pulled them back from the edge. Giant Tortoises, like their home itself, are experiencing a period of renewal unlike any they have witnessed in the last four centuries, but threats such as climate change, wildlife trafficking, and introduced invasive species are threatening to upset this newly rediscovered peace.

The challenges that Giant Tortoises, Galápagos, and our planet now face are complex and existential, but we are driven to find the innovative and sustainable solutions necessary to protect the incredible Galápagos Archipelago. Still, we can’t do it alone. All that we have achieved was only possible thanks to the generosity of a dedicated international community of supporters and donors who stood with us every step of the way. Looking to the future, we need their help, and yours, more than ever.