The Presence of Whale sharks is a Good Indicator of a Healthy Marine Ecosystem

“Exploring the underwater world has been one of the most rewarding and enriching aspects of my life and I feel I owe this to the environment and the oceans that have given me so much.”

-Jonathan R Green, Founder and Director of the Galapagos Whale Shark Project

Galápagos Conservancy, in collaboration with our partners, offers the opportunity to receive grants for sustainability and/or conservation actions to protect the Galápagos Islands.

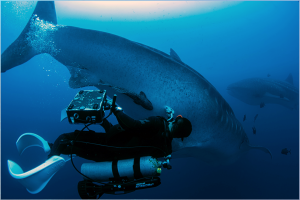

Our partner Jonathan R. Green, a permanent resident of Galápagos, is carrying out research with the Galápagos Whale Shark Project, that will provide reference data regarding the reproductive status and movements of Whale Sharks in the Galápagos archipelago— information that is essential for conservation management.

Whale sharks are plankton patrollers – these filter-feeding sharks can eat more than 20 kilograms a day! When ocean waters are rich in plankton, it shows the water is full of nutrients and the ecosystem is healthy. Since Whale Sharks prefer waters packed full of plankton, their presence is a good indicator of a healthy marine ecosystem.

Whale Sharks also regulate the ocean’s plankton levels and prevent these microscopic organisms’ numbers from growing without restriction – something that could have a negative effect on ocean environments. Therefore, the importance of having the greatest amount of information possible to contribute to the conservation of this emblematic species can’t be overstated.

- Where are you from and how long have you lived in Galápagos?

I am originally from the UK but lived in France and Spain and moved to the Galápagos in 1988. - Help us to understand more about this species, what is the difference between a Whale and a Whale Shark?

This is a common misconception, that whale sharks are mammals. They are the largest of all fish, the greatest of all sharks, living, and past, and of course do not need to surface to breathe but can remain indefinitely submerged. But although they are not mammals, they are viviparous, incubating the eggs internally and giving birth to live young. Perhaps also due to their size, they are often confused with whales.

- Why are you so passionate about Whale Sharks?

Since my first encounter with a Whale Shark, they have captivated me. As a child, I wondered what meeting a living dinosaur would be like and this is what whale sharks are, as they have roamed the oceans for over 70 million years. They are huge animals, the greatest shark to ever live and yet they are such gentle giants. - Let’s focus on the project: why is it necessary to study the reproductive status and movements of Whale Sharks in Galápagos?

Knowing such facts as where a species breeds and where the young live, where they feed, and what habitats they frequent are the key factors to understanding a species. Unless we understand them we cannot hope to protect them either in the short or long term. As a species in danger of extinction the need to study them is now a matter of urgency. It seems that the population of Whale Sharks visiting Galápagos are mostly adult females, a completely different scenario to all other aggregations worldwide. This presents us with a unique opportunity to learn specifically about their reproductive status. - How do you feel doing this work and why do you do it?

Being able to work with animals like Whale Sharks is tremendously exciting and yet at the same time daunting as much of the science we are carrying out is new and we are constantly changing and developing techniques in order to achieve new goals. Exploring the underwater world has been one of the most rewarding and enriching aspects of my life and I feel I owe this to the environment and the oceans that have given me so much. I would like to give back to the planet and hope that I am able to make a difference towards a future with healthy oceans, hopefully, one where sharks, in general, are protected and no longer massacred in their millions each year. - What excites you the most about the Whale Shark?

They are one of the greatest mysteries of the Oceans. Diving with them is a privilege that few humans are able to experience. - In your experience, what makes Whale Sharks hard to study?

Because of their size, many field techniques are not applicable. They also roam huge areas of the ocean and spend most of their lives far from those places we humans are able to access in order to study them.

- Why are the reproductive behaviors of Whale Sharks so mysterious and difficult to study?

No one has yet seen a Whale Shark mate or give birth. We are not really sure where these events take place. The greater part of their lives is spent in pelagic oceanic areas out of sight. Even with modern technology, it is not possible to follow them as they dive to great depths and remain submerged for long periods of time. - Why have you chosen the Galápagos Islands as the home base for your research on Whale Sharks?

I worked for many years as a Dive Master in the Galápagos and it was during this time that I began to observe them at Darwin Arch in the far north of the Galápagos Archipelago. The opportunity was there to study them and no one was doing it so I began what I thought would be a short field investigation. That was over 15 years ago and I believe we still have a long way to go before we find all the answers to the questions we have.

- Why do Whale Sharks migrate and where do they migrate from and to?

Whale Sharks make seasonal and possibly annual or multi-year movements that we believe to be associated with basic necessities, namely food, and reproduction. Like many other species, they travel in order to find food and a mate. We have used satellite tracking devices to follow them as they depart from Darwin Island and have found connectivity with certain areas of the Eastern Tropical Pacific. They frequently move towards the mainland of Ecuador and travel south to the edge of the continental shelf off Peru. As the waters of this area are extremely rich in plankton we believe this is food related. They may find mates in this area too. The biggest question is where they might be giving birth and where the young live for the first years of their lives.

- Since the Galápagos Whale Shark Project conducted the first-ever ultrasounds of Whale Sharks in 2018, how has your research progressed? What have the results of those ultrasounds allowed you to study?

The first successful ultrasound data from Whale Sharks in a free swimming environment was an enormous achievement. The data showed egg follicles but not embryos, so is not conclusive with regards to pregnancy. The immediate result shows that this is a valid procedure for field work and that we will get more results using ultrasound. Due to the limited time we have for fieldwork and the hiatus caused by the pandemic we hope to resume this work in July of this year.

- Three females off the Galápagos Whale Sharks were studied, aiming at teasing apart one of the ocean’s greatest mysteries: how they mate and where they give birth. Can you share some results of that investigation?

We successfully tagged 8 female Whale Sharks, including 1 juvenile this season. We have gathered an incredible data set from these tags but sadly three of the satellite tags have transmitted from land; two from Ecuador and one from Peru. This has highlighted a disturbing level of interaction between this species and the fishing fleets from both countries. As these SPLASH10 tags do not float they have to be removed from the animal and transported by humans to land. What we are trying to ascertain now is whether this is from the entanglement of Whale Sharks with fishing gear or if they are being landed for illegal commerce. The tracks of all the tagged Whale Sharks help us to build up a detailed “map” of local and regional movements within the ETP. What the new SPLASH10 tags give us is depth and dive data which also allows us to better understand habitat use and possible foraging and breeding behavior. - In your investigation you also mention that there is a new urgency in recent years, we’re losing animals at a rate which is unprecedented in the history of planet Earth, is this the case of Whale Sharks too?

Since the 1980’s Whale Sharks have gone from bycatch to a targeted species, increasing dramatically in the 1990s and beginning of the millennium. As other shark species decline from indiscriminate fishing, Whale Shark oil and fins are of increasing value despite their “protected” status. - The Whale Shark is listed by the IUCN as Endangered. Worldwide, what are the population trends? What are the major threats to the species?

Global data indicates a general decline in all Whale Shark populations that are currently being monitored or studied but like so many other pelagic mega marine fauna, exact figures are extremely hard to estimate. Threats are all anthropogenic, illegal fishing, bycatch and entanglement, vessel strikes and plastic pollution. Many of these are silent and invisible killers that pass unseen and unrecorded.

- Regarding the new study you’re carrying out, how the data about the reproductive status and movements of Whale Sharks in the Galapagos archipelago will contribute to conservation efforts?

The data we started collecting over a decade ago has already been incorporated into management policy and plans within the GMR. Satellite data showed conclusively the level of connectivity with other island ecosystems such as Cocos and the ETP in general. This work together with work carried out by a number of scientists was used just this year to support the extension of the GMR and the creation of the new Galápagos – Cocos Swimway. As work progresses we hope to be able to identify or indicate those areas key to the survival of the species, where they are foraging, where they are breeding and where they give birth. We are still struggling with the available technology and limitations on field work in order to achieve our goals but as with all research and science, we understand the need for long-term studies. - What is the current status of your investigation carried out with the Galapagos Conservancy support?

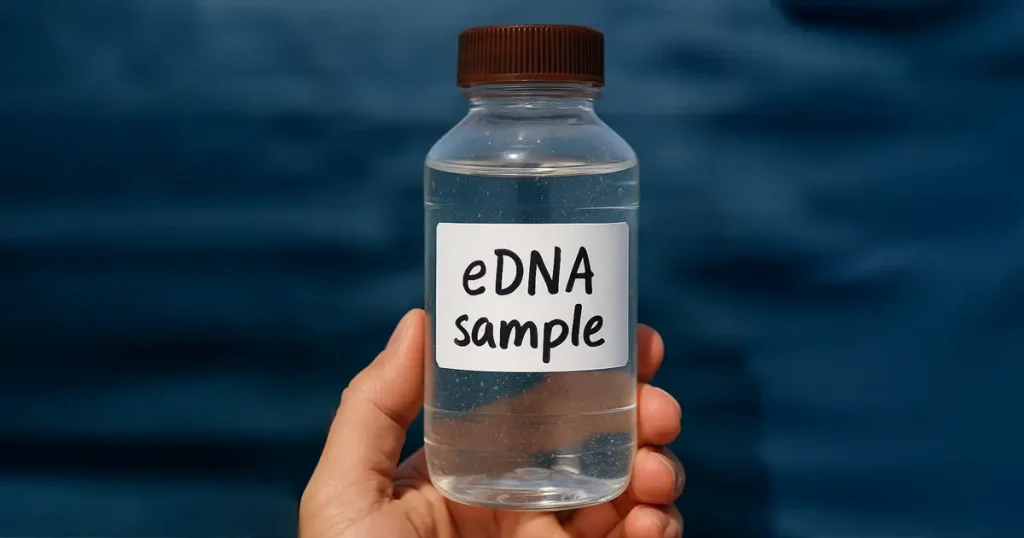

During the first four months of the year, the project has advanced in data wrangling and the formation of metadatabases for the analysis of movement ecology and diving behavior of Whale Sharks for the past decade. The next months will serve for data analysis and manuscript writing. The project has also advanced in the collection of photo-identification from dive guides, fishermen, passengers and scientists of the reserve. In total we have collected 39 new encounter reports assigned to 16 new individuals and 1 re-sighting. The individual re-sighted was first reported in Galapagos in July 2008 and re-sighted in January of 2022. The work to be done with ultrasounds in the Galapagos seems to be impacted by COVID-19 travel restrictions. Our partners from the Okinawa-Churaumi aquarium cannot travel internationally due to restrictions imposed by internal regulations. Considering they are the only people trained to run underwater ultrasounds on whale sharks and the only ones with the equipment to do so, this strongly impacts this portion of our research goals for this year. For the reproductive study, the team will make it a priority to take blood samples as an indicator of possible pregnancy, and continue with ultrasound work next year.

Regarding Environmental Education- Involvement of the Local Community, talks have been given to the community through various platforms. - You have probably dived many times near this majestic species, do you have any experience that you will never forget?

I have been fortunate over the years to dive hundreds of times with Whale Sharks. I will never forget the first time I saw one at the end of a dive in 1990. It was a pivotal moment in life that set me on the path of creating a project to study Whale Sharks. Nonetheless, every dive that I encounter with a Whale Shark is an equally amazing experience. Seeing this with other divers, their first encounter and the excitement this brings is deeply gratifying. Being able to have this experience with my three children is one of the greatest gifts of life. Recently I felt I was able to give back in a very physical way as I managed to cut a big piece of fishing net off the pectoral fin of a Whale Shark and free it from this horrific and potentially fatal burden. - What would be your message to the world regarding this spectacular species, the Whale Sharks?

Whale Sharks have existed on this planet since the bygone era of the dinosaurs, probably over 70 million years. They are a living dinosaur, an icon of the oceans and as with so many of these mega marine species, crucial to ocean health.

It is only since the arrival of modern humans that their future is threatened. They have as much right to exist, survive and thrive as we humans do and as such they should be respected, protected and allowed to continue as they have done for millions of years in a healthy environment, as healthy oceans are as necessary to this planet and our future as the air we breathe.

During the first four months of the year, the project has advanced in data wrangling and the formation of metadatabases for the analysis of movement ecology and diving behavior of whale sharks for the past decade. The next months will serve for data analysis and manuscript writing.

The project has also advanced in the collection of photo-identification from dive guides, fishermen, passengers and scientists of the reserve. In total we have collected 39 new encounter reports assigned to 16 new individuals and 1 re-sighting. The individual re-sighted was first reported in Galápagos in July 2008 and re-sighted in January of 2022.