Vanished Without a Trace? The Galápagos Damselfish and the Legacy of the 1982–1983 El Niño

A new scientific study has raised the alarm: a small reef fish, endemic to the Galápagos Islands and unseen for more than 40 years, may have gone extinct.

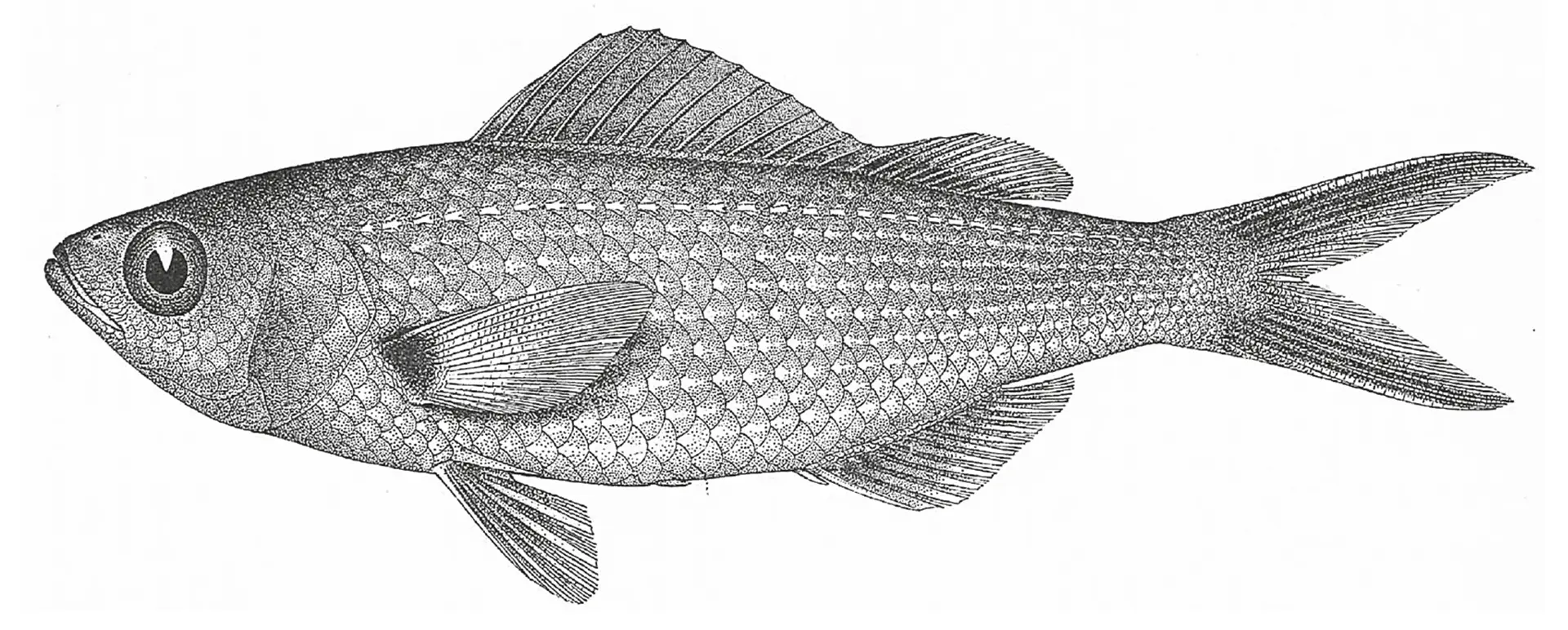

The Galápagos damselfish (Azurina eupalama) was once a common sight along the archipelago’s rocky coasts. But after the devastating El Niño event of 1982–1983, it disappeared. Today, its absence is more than a biological loss—it’s a warning we can’t ignore.

The El Niño That Changed Everything

The 1982–1983 El Niño was, at the time, the most intense ever recorded. Ocean temperatures around Galápagos rose as much as 8°C (14°F) above normal. Cold currents stalled, plankton crashed, and with it, the entire marine food web.

The impacts were dramatic: millennia-old coral reefs died, marine iguanas stopped reproducing and shrank in size, and sea lions lost or abandoned their pups. It was an early signal of how vulnerable island ecosystems like Galápagos are to climate disruption.

Some species eventually recovered. The Galápagos damselfish did not.

A Shimmering Jewel Lost to the Current

According to a 2025 study by scientists Jack Grove and Benjamin Victor, the damselfish was a planktivore uniquely adapted to cool, shallow waters. From its discovery in 1898 until the late 1970s, it was consistently documented in marine surveys—an established part of Galápagos biodiversity.

But after 1983, it simply vanished.

Despite decades of searching by scientists, naturalists, divers, and underwater photographers, not a single individual has been seen. The species’ ecological niche may have been so specific—and its population so localized—that it could not withstand the sudden shift in its environment.

A Future Full of Warnings

The disappearance of the Galápagos damselfish may be the first documented extinction of a tropical marine fish driven by climate-related ocean change. For over four decades, researchers have searched the places the damselfish once called home. But it’s no longer there.

And this may not be an isolated case. As the planet warms, extreme climate events like El Niño are becoming more frequent, more intense, and more prolonged. Ocean temperatures are rising at record-breaking speeds. In 2023, global sea temperatures hit their highest levels in recorded history—for the fifth year in a row.

This trend threatens species like the damselfish—endemic, specialized, and confined to small, isolated populations. These are the very qualities that make Galápagos so extraordinary—and so vulnerable.

“The loss of the Galápagos damselfish is cause for concern. While it involves a single species, it may also reflect broader ecological shifts underway in our oceans. Without further attention and action, similar declines could occur in other species. “—Dr. James Gibbs, Vice President of Science and Conservation, Galápagos Conservancy

A Legacy of Dedication—and a Search That Never Gave Up

The story of the Galápagos damselfish is also tied to the legacy of Godfrey Merlen, a pioneering scientist and conservationist who devoted his life to Galápagos marine life. For more than five decades, Merlen lived on the islands, explored their coastlines, documented their species, and mentored generations of researchers and naturalists. He passed away in 2023, never having found the damselfish again.

In his later years, he led a dedicated search for the damselfish, joined by local guides and fellow scientists. Though no sightings were made, his work laid a vital foundation for future efforts—and left a lasting mark on the scientific community.

At Galápagos Conservancy, we are proud to have worked alongside him. His legacy fuels our mission: to collaborate with scientists, communities, and local partners to protect what still can be saved. Because as Godfrey believed conservation depends on persistence—and working together.

Let This Loss Mean Something

Yes, the damselfish was small. But its disappearance signals something much bigger. We’re entering a time when species may vanish quietly, without a trace—unless we act.

That’s why Galápagos Conservancy is doubling down on our commitment to science, restoration, and prevention. Mourning is not enough. We must anticipate. We must protect.

Every species lost is a page torn from the book of life. But there’s still time to write a different ending. Let this story move us. Let it motivate us. Because we can still make a difference—if we choose to act.

Sources Consulted

- ETESA (Panama’s Hydrometeorology Office). During the 1982–1983 El Niño event, sea surface temperatures around the Galápagos Islands and along the Ecuadorian coast rose from approximately 22 °C to nearly 30 °C.

View report (PDF) - Nature (2024). A recent article reports that the world’s oceans absorbed more heat in 2023 than in any other year on record, marking the fifth consecutive annual high.

Read article - WWF (2011). During the 1982–1983 El Niño, an estimated 97% of Galápagos reef-building corals died, severely affecting local marine ecosystems.

View document (PDF) - Laurie, W.A. (1990). On Santa Fe Island, marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) experienced approximately 60% mortality between March and August 1983, primarily due to food scarcity following changes in marine algae.

ResearchGate - Trillmich, F. & Limberger, D. (1985). The 1982–1983 El Niño caused increased pup mortality and reduced reproduction in Galápagos sea lions (Zalophus wollebaeki) due to food shortages linked to marine warming and productivity collapse.

ResearchGate - Grove, J., & Victor, B. (2025). Rediscovery Potential of the Galápagos Damselfish Azurina eupalama: A Case Study in Tropical Marine Extinction Risk Assessment.

ResearchGate.

Share: