Scalesia: The Giant Daisy Trees of Galápagos

by Aaron Provencio

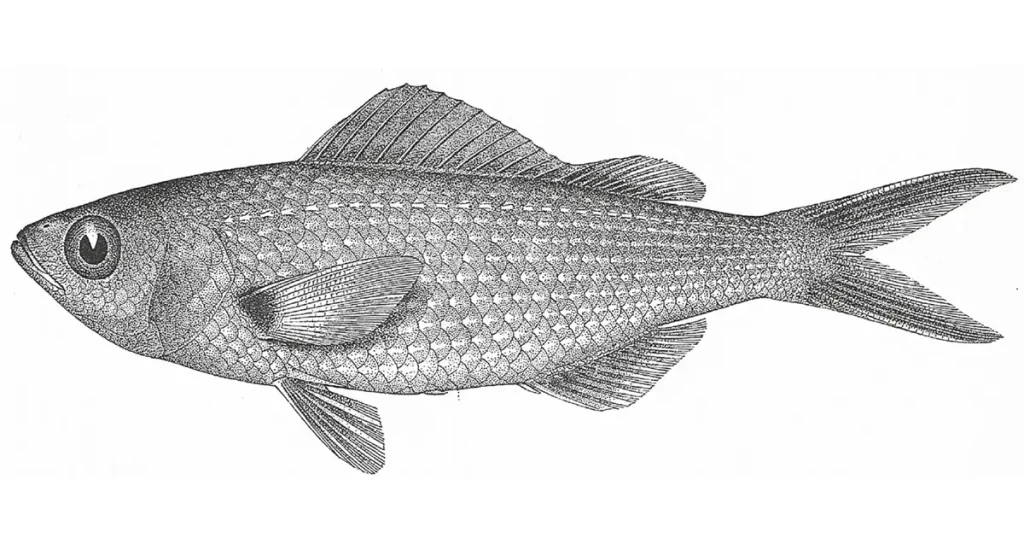

The Scalesia genus is — like so many other members of the Galápagos biological community — both completely unique but also a strange and distant twig on the complex tree of life. Consisting of 15 species of trees and shrubs that are found nowhere else in the world but the Galápagos Archipelago, Scalesias — some of which are widely distributed across the Archipelago and others that are only found on certain islands — are even more unique given their membership in the Asteraceae family, a taxonomic grouping shared with daisies, sunflowers, lettuce, and some 32,000 other known species of which almost zero grow as trees. But here in Galápagos, they have spread to survive and thrive in many different vegetation zones throughout the Archipelago, including the “Scalesia habitat zone” found in the moist highlands of certain islands including Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal, and Floreana.

How then did this singular genus develop from a family of small herbaceous plants into — at least in the case of the Scalesia pedunculata or Giant Daisy Tree — dense stands of tall, slender trees capable of covering entire landscapes? We owe that, as with most everything else in Galápagos, to the incredible power of evolution.

Some time ago, long before human beings set foot on the Galápagos Archipelago, a seed or seeds from a landlocked species of the family Asteraceae landed in the virgin volcanic soils of Galápagos. As time passed, these plants evolved to fill the empty ecological niches provided to them by the sparsely colonized landmasses of the Archipelago and took on forms and functions that their mainland counterparts could only dream of. This extreme modification for adaptation is referred to by evolutionary biologists as “adaptive radiation,” and because of this some refer to the Scalesia tree as the “Darwin’s Finch of the plant world.”

Stands of Scalesia grow as a cohort — groups of similar age who often match each other in both height and condition. This means that entire populations grow and reach the age of maturity — around 15 years— at the same time. This group-growth trait likely adapted as some sort of stand survival method, but it also means that entire forests can go more than a decade without seeding to reproduce. If a cataclysmic event — such as a major storm or landslide — causes an entire forest to collapse, there may be no established seed bank there to regrow the lost trees.

Just like the forests of mainland South America, the Scalesia forests of Galápagos are incredibly biodiverse habitats that house a striking number of endemic plant and animal species — including the iconic Galápagos Giant Tortoise and some of the world’s rarest birds. On Santa Cruz Island, the Scalesia forests are home to the Darwin’s Flycatcher, known in Spanish as the Pajaro Brujo. These birds rely heavily on the forests for survival, but the rapid clearing of Scalesia in the name of agriculture has led to a matching decline in Flycatcher populations over the years. In addition to deforestation, these forests are under intense threat from invasive species such as Guava and Hill Raspberry. Today, only a few scattered patches of forest remain.

Managing and restoring the Scalesia forest is a difficult task as invasive species such as the Raspberry regenerate rapidly, are fast-growing, and have large seed banks in the soil even when the plant itself is removed. The preservation of the Scalesia is absolutely critical to the ecosystems of Galápagos and the wildlife that inhabit them.

In order to reverse the damage that habitat loss has inflicted on native species, we have partnered with Celebrity Cruises and the Galápagos National Park Directorate on a joint forest restoration initiative that has given Celebrity staff and passengers the opportunity to plant more than 50,000 Giant Daisy Trees on Santa Cruz Island. Since 2014 this partnership has led to the ongoing restoration of almost 50 acres of forest and benefitted the countless plant and animal species that rely on the Scalesia for survival.

Although we still have a ways to go to ensure the long term survival of the Scalesia forests, regenerative practices like this are a critical next chapter in the story of the Giant Daisy Trees of Galápagos.