Rediscovering the Giant Tortoises and Magical Landscapes of Alcedo Volcano

By Wacho Tapia, Director of the Giant Tortoise Restoration Initiative

Alcedo Volcano is located in the center of Isabela Island, the largest island in the Galápagos archipelago. It has one of the most spectacular landscapes on the planet, where one can witness both the volcanic activity that gave rise to the Islands as well as the ecological and evolutionary processes in full action — such as the opening of paths created by giant tortoises.

Alcedo was once home to a wide variety of species of plants, shrubs and trees, all of them native and endemic. But this volcano is in the process of ecological restoration after introduced feral goats almost brought its ecosystems to collapse, thanks to their voracious appetites that led to the destruction of many plant species over several decades. This affected the endemic giant tortoise populations there, which are also herbivorous but do not have the same capacity for movement and reproduction as goats. I personally witnessed how the presence more than 100,000 goats led to terrible soil erosion and habitat destruction, relegating the once dense and beautiful forests of Alcedo to a kind of semi-desert.

Fortunately, steadfast conservation efforts led by the Galápagos National Park Directorate, with the support of many organizations and individuals, is now coming to fruition. In 2006 the eradication of goats was achieved, not only from Alcedo but from all volcanoes in northern Isabela Island. This historic conservation action — Project Isabela — involved a massive ecological restoration project through the eradication of invasive donkeys and goats; probably the best developed and also the most ambitious on the planet.

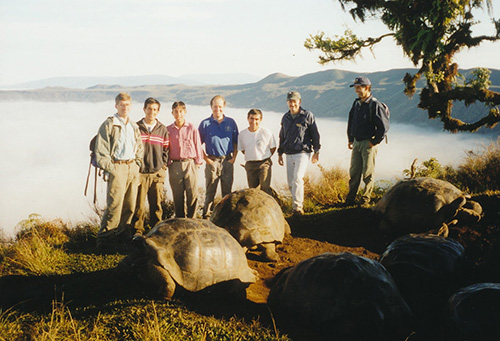

I have a special connection with Alcedo volcano: in addition to being one of the most beautiful places I know, it is where exactly 24 years ago, in February of 1997, I ascended the 11 miles of the volcano’s intricate path to the summit with a 130-pound backpack and infinite wishes of leaving a positive footprint, to start my first day of paid work as a biologist and Park ranger. It was also at this volcano that my wife and I learned some of the happiest news of our lives: that our first daughter (now a biologist too) was on the way.

Now in January of 2021, overcoming the difficulties of the pandemic that is affecting all of humanity, with more than two decades of experience and the same desire to do the best job possible, I had the opportunity to return to the volcano — this time with an incredible team of park rangers and volunteers. Our primary goal was to assess the state of the ecosystems and particularly of its key species, the iconic giant tortoises.

It was a little more than a week of extreme effort, with some days of intense rain and others of strong tropical sun, walking an average of 18 miles a day. But it gives me immense satisfaction to report that Alcedo is recovering its evergreen forests at the summit; the magic of its endemic guayabillo forests at mid-altitude; the mystical dry forests in the lower areas and the monospecific stands of ferns on the slopes near the summit. We were also able to confirm that the tree fern (Cyathea weatherbyana) endemic to the high and humid lands of Galápagos, and believed to be extinct in the volcano, is slowly returning. We registered eight individual tree ferns; the majority inside two fences that were built to save them from goats. But I am sure that in a few years it will once again dominate the landscape in the southeastern part of the summit, as it was before the goat invasion.

The most gratifying part of this expedition was to be able to verify that, after the plant communities, the giant tortoises have perhaps benefited the most from the eradication of the invasive herbivores. By not having such strong competition for food from the goats, and no longer having their nests trampled or destroyed, their population has grown significantly — from approximately 6,000 to perhaps more than 15,000 individuals, with a large number of juveniles between 12 and 15 years of age. Which makes sense: when the vegetation recovers, the survival rate of juveniles must be much higher than when the goats were there. We will surely verify this once we process the data of the almost 5,000 tortoises that we tagged during our systematic surveying during the expedition. I am extremely grateful for the efforts of the entire expedition team and the generosity of Galápagos Conservancy’s donors, who helped make all of this possible.