Can the Galapagos marine ecosystem rebound from repeated bouts of El Niño stress?

Whether the Galapagos marine ecosystem can rebound from the stress caused by El Niño is a key question that our research team is aiming to answer, with the support of Galapagos Conservancy, by monitoring bottom-dwelling communities of marine invertebrates and reef fish at 12 sites in the Galapagos Islands and by conducting underwater experiments. After a productive summer of dive-based research, our team, consisting of myself, PhD Candidate Robert Lamb, and undergraduates Maya Greenhill and Calvin Munson, returned to Brown University, while our colleagues Franz Smith and Alejandro Perez-Matus returned to New Zealand and Chile, respectively. We all brought back hard drives filled with pictures, videos, and data on the state of the subtidal marine ecosystem.

We’re adding this most recent survey data to our 19-year baseline to test our roller coaster conceptualization of how the spectacular marine life of Galapagos rises and falls as it is impacted by El Niño – La Niña cycles (El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO). With its unusually high temperatures and scarce planktonic food, El Niño represents the downhill phase of the roller coaster — a period of high stress potentially decreasing population numbers and the diversity of bottom-dwelling (benthic) organisms. The change in temperature causes corals to bleach and eventually starve and die as they expel the brownish-green photosynthesizing algae in their tissues. Many Galapagos marine animals die or cannot reproduce successfully due to the lack of food.

The ecosystem appears to bounce back to a certain degree when cool, nutrient-rich waters of La Niña return, pushing the system back uphill on the rollercoaster, demonstrating resilience to a reoccurring climatic shock. The big question is: will the subtidal benthic and reef fish communities be degraded after the intense sequence of three (and counting — there is a 70-75% chance of another El Niño occurring in Galapagos in January-April 2019) recent ENSOs, or will unexpectedly high levels of resilience during La Niña enable the ecosystem to once again recover to its original, biodiverse state?

The jury is still out as resilience, which depends on the intrinsic capacities of organisms to reproduce, recolonize habitats, grow, and recover from stress, takes time to measure.. By surveying permanent coral plots in January and in August this year, we found that more finger corals bleached and died during the strong 2014-2017 ENSO cycle than the massive coral species, Porites lobata, that resembles Chinese pagodas or flattened shingles. The overall rate of coral bleaching was lower than during previous ENSOs since 1999, which is curious, as the most recent El Niño was the strongest in this period. Some of the massive P. lobata corals bleached and recovered in 8 months (see photo below), demonstrating unusually high resilience.

Monitored coral plots showing remarkable resilience to ENSO bleaching in the coral ‘Porites lobata.’ Photo at left shows the coral in a bleached state towards the end of La Niña in January 2018. Photo at right shows the same colony in a recovered state 7 months later with its complement of symbiotic brownish green photosynthesizing algae in its tissue. (© Jon Witman)

The “barnacle booms” of the 2017 La Niña continued into 2018. As of early 2018, 83% of our monitored sites were in a barnacle reef state where most of the rocky bottom down to 15-m depth was covered with big Megabalanus sp. barnacles. We think that these barnacle booms occur during La Niñas due to high reproduction when the phytoplankton that the barnacles eat becomes super-abundant. Since these barnacles are an important food source for lobsters and many fish species, La Niña barnacle booms may also boost upper levels of the Galapagos marine food webs, helping them to rebound following El Niño food shortages.

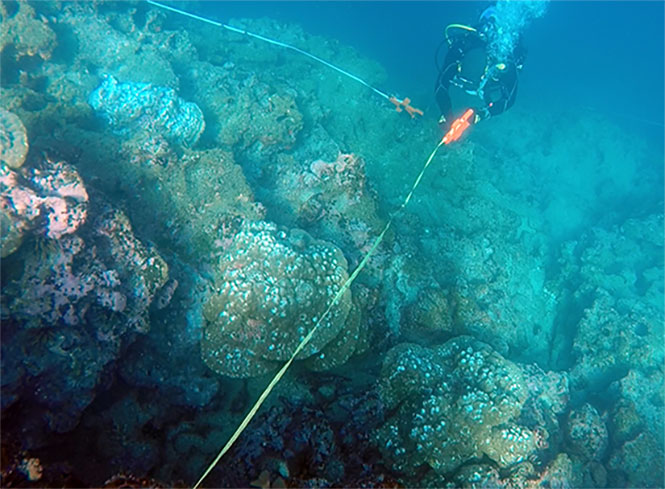

Swimming 1-2 meters above the bottom-dwelling barnacles, corals, sponges, and sea urchins, Robert Lamb counted and sized reef fish adjacent to 50-meter-long transects at all sites. He also assessed fish abundance and diversity with Go Pro cameras placed at the sites between dives (when divers weren’t present). Robbie’s data indicated La Niña resilience as well. Fish abundance, which declined during the 2016 El Niño, had increased sharply by the end of La Niña in 2017 and remained high in 2018. This was largely due to the recovery or return of planktivorous fish.

With marine invertebrates and fish rebounding during La Niña, we think we’re seeing a rare type of resilience across the broad spectrum of the animal kingdom — possibly by the same mechanism. Thankfully, we found that two surprising signs of ecosystem stress that we discovered during the January 2016 El Niño — an ulcerating skin disease affecting 18 species of reef fish, and a proliferation of rubbery mats of brown cyanobacteria across one third of the bottom at Cousins Rock — were short-lived and had virtually disappeared by our latest surveys in August 2018.