From the Desk of Dr. James Gibbs: On the Return of the Floreana Giant Tortoise

Some moments in conservation stay with you.

One such moment for me is inseparably tied to a visit to Wolf Volcano in 2000. At the time, the Floreana giant tortoise had been considered extinct for nearly 150 years — the first giant tortoise species lost from Galápagos following relentless exploitation and the impacts of introduced, invasive species. Charles Darwin himself had recorded their decline during his 1835 visit, among the last scientific witnesses to a lineage slipping toward disappearance.

During the final expedition of a five-year project to make the first survey of all giant tortoise populations in the Islands, we encountered something unexpected on Wolf Volcano on Isabela: tortoises with saddleback shells. Looking back at my field journal from that fateful expedition, I wrote:

“This morning we headed up the old hunter’s trail and, much to our surprise, where there were no tortoises the few days before suddenly they were all over. There were tiny ones and big ones, males and females, tortoises all over…we then got serendipitously sidetracked and found ourselves in the thick of many highly sculpted and saddle-backed tortoises on a side slope to the volcano.”

This was odd, because the tortoises native to Isabela Island have dome-shaped shells. So we wondered whether these tortoises came from elsewhere. Historical records suggest that sailors once moved tortoises between islands, leaving some behind. We were shocked when subsequent genetic testing confirmed what we had barely allowed ourselves to hope. These animals were hybrids with significant Floreana ancestry.

The Floreana tortoises, it turned out, had not vanished completely.

That discovery revealed a narrow but meaningful opportunity. Working with the Galápagos National Park Directorate and our partners, we began a focused breeding program at the Santa Cruz Island breeding center. Our goal was not to resurrect Floreana’s past tortoise exactly as it once was; that would be impossible. Our goal, instead, was to produce tortoises capable of once again performing the ecological role their ancestors had carried out on Floreana.

That discovery revealed a narrow but meaningful opportunity. Working with the Galápagos National Park Directorate and our partners, we began a focused breeding program at the Santa Cruz Island breeding center. Our goal was not to resurrect Floreana’s past tortoise exactly as it once was; that would be impossible. Our goal, instead, was to produce tortoises capable of once again performing the ecological role their ancestors had carried out on Floreana.

This February, that long-awaited opportunity became a reality.

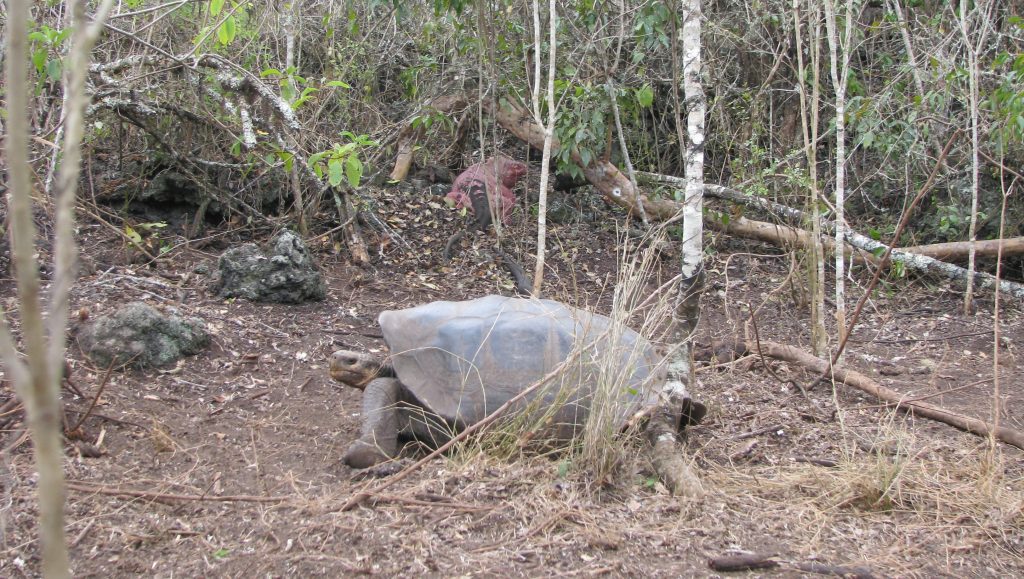

For the first time in 180 years, Floreana lineage giant tortoises set foot on Floreana Island once again. On February 20, 2026, 158 young tortoises were released into their ancestral habitat, marking a historic milestone in one of the most ambitious ecological restoration efforts ever undertaken in Galápagos.

Over more than two decades, hundreds of juveniles were bred and raised under managed care. They grew for 12 to 14 years, monitored carefully until they reached a size large enough to withstand current pressures in the wild. Their release was carefully timed with the rainy season, when vegetation is most abundant and environmental conditions are most favorable for them to thrive.

Now, they are home.

This release is part of the Floreana Island Ecological Restoration Project, a collaborative, multi-decade initiative designed to restore ecological integrity while supporting a sustainable future for the island’s approximately 160 residents. The tortoise return represents the flagship and first in a series of 12 species restorations planned for Floreana as conditions allow.

The return of giant tortoises is foundational to that vision.

Giant tortoises are keystone species and ecosystem engineers. Through grazing and long-distance seed dispersal, they shape plant communities, influence how vegetation is distributed across the landscape, and benefit soil processes. Their absence fundamentally altered Floreana’s landscape. Their return restores a missing ecological process that supports native plants, birds, and broader biodiversity.

In many ways, this is where restoration becomes reality.

Each tortoise now carries a lightweight GPS transmitter, allowing our team to monitor movement, habitat use, and health in real time. Annual monitoring will guide adaptive management as additional releases — approximately 25 to 100 tortoises per year — explore their new home and build toward a self-sustaining population over the coming decades.

Some have asked whether these tortoises are “original” Floreana tortoises. No verified individuals of the extinct species remain. The animals released are hybrids descended from the extinct Floreana lineage and a closely related population. Because the many hybrids collectively retain much of the original genome of the Floreana tortoise, reintroducing them will allow natural selection to shape them toward—though never exactly replicate—the original tortoise form. They are similar in form, behavior, and ecological role to the original tortoises that once roamed the island, and that role is now what matters most.

As tortoises move across Floreana’s volcanic terrain, they will disperse seeds, open habitats, and help rebuild ecological processes that have been absent for nearly two centuries. As vegetation recovers, conditions improve for native birds. Seabirds, in turn, will transport marine nutrients onto land, strengthening the connection between terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

Equally important is the role of the community. Floreana was one of the first inhabited islands in Galápagos and suffered significant biodiversity loss as a result. Today, its residents are central to this restoration effort. From biosecurity measures to long-term stewardship, ecological recovery and community resilience are advancing together.

The work underway on Floreana is emerging as a model for restoring inhabited islands worldwide. Most islands across the globe face similar pressures: invasive species, habitat degradation, and the challenge of balancing conservation with human livelihoods. What is unfolding here demonstrates that large-scale restoration is possible, even in complex, lived-in landscapes.

For me, watching these 158 tortoises back in their ancestral home again, slowly exploring their habitat for palatable plants to eat, shady spots to get away from the intense sun, and depressions where water might collect during the next rain and provide them a drink, brings that 2000 discovery full circle. What once seemed like a faint genetic echo has become a living population.

This moment reflects patience, science, partnership, and sustained commitment. It shows that even after 180 years, recovery is possible. This release is not the end of the story. It is the beginning of a new chapter, one that will unfold over decades and centuries as tortoises once again shape the landscapes, of Floreana Island and many other islands of Galápagos.

Rediscovering a lineage is rare. Restoring one at this scale is rarer still.

And for those of us who stood on that volcanic slope 26 years ago, it is a powerful reminder that sometimes, what seems lost forever is simply awaiting the chance to return.

For Galápagos, always,

Dr. James Gibbs

Vice President of Science and Conservation

Galápagos Conservancy

Share: